On long flights, I miss the Internet. I daydream of connected screens. The luminous and animated images at our disposal lack the liveness we’ve been accustomed to. I barely feel part of the world this way. Touch the screen or press any key on the handset to activate the screen But all it leads to is a static menu.

More than accustomed, it would be more accurate to say that we got acclimated to this perpetual connectedness. Touch the screen or press any key on the handset to activate the screen keeps blinking.

My phone is lifeless because it’s liveless; no notification in sight.

Its screen feels, to me, useless. The entire machine, actually, loses its appeal.

Next to me, a girl in a pink sweater just pictured the seat-back screen facing her that displays a slightly elevated back view of our plane. It’s true that she’s a little far from the window. The day rises and she admires it by proxy. The tail camera's here for that. For us all to get the exact same outlook. A view that no human eye can actually enjoy on its own.

And the girl looks through my window and I look at her. I don’t know if she sees me. Then the screen catches her attention again.

I find myself thinking back on Bret Easton Ellis’ Imperial Bedrooms, in which phone LEDs keep blinking. It’s a novel of constant notifications. I remember how outdated it felt to me when I read it, even though soon after its publishing. Emphasizing signs of the times too much puts them at a distance, feeling like a media archaeology of the present.

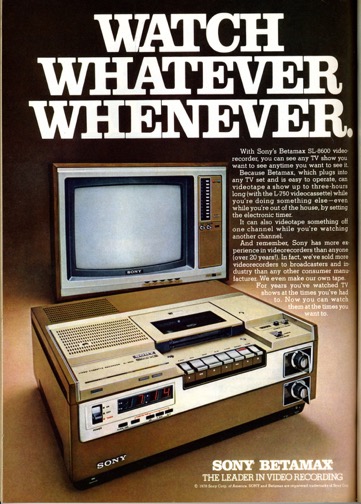

The book is a tweny-five-years-later sequel to Less Than Zero in which the characters left each other notes to tell them someone called them on the phone while they were not home, and had to rush upstairs to answer it when it rang again. And when they knew they’d miss a movie on TV, they recorded it on their VCR.

Surprisingly enough, and although the VCR sounds like an age-old device, its production definitely stopped only two years and a half ago. If the first patent dedicated to a video recording machine dates back to 1927, the domestic use of this appliance was legalized in 1984 (by way of a first commercialization intended for professional use in the 1950’s) after eight years of intermittent legal fights known as the Betamax Case culminating in the Supreme Court ruling that taping copyrighted broadcasts for one’s personal use didn’t constitute a violation of copyright law and that the companies producing the VCRs could not be held liable for possible infringements. In other words, when Ellis’characters, who are the offspring of Hollywood producers, talk about recording movies on their VCR, in 1985, they’re bridging the gap between the film industry wary of the spreading of this new technology and the enthusiastic millions of households freed from the networks’ broadcasting schedules that were enjoying movies at home whenever they felt like it and TV shows without ads since they could fast-forward through them.

The revolutionary aspect was indeed this one: you could watch a show after the fact. Television was freeing its viewers from the constraints of live watching, after having freed itself from the constraints of live broadcasting in the late fifties thanks to the professional video tape recorders. Until then, what mattered was the direct connection between the broadcaster and the audience, and if you needed to do anything but didn’t want to miss any minute of the show you were watching, you had to wait for the ad break.

So with the advent of the VCR, suddenly, the event was in the disconnection from the live, in the idea of the audience getting the content at its convenience, which of course may differ for every individual.

But what did it mean and what did it feel like to watch TV after the fact? While it was empowering the viewer with a sense of individuality among the masses and with a sense of agency over the media, it also laid the groundwork for today’s on demand technologies such as VOD services and streaming television (YouTube, Amazon Video, Netflix, Hulu, and so on), but also podcast when it comes to the radio. The technical term for this is “time shifting”, which obviously sounds like a superpower.

But think of it more carefully. Without a few million other people watching the same thing as you at the exact same time as you, don’t you feel a bit isolated? Don’t these moving images look like dead moving images? With the loss of the feeling of communion associated with live broadcasting, time shift broadcasting and the possibility of recording or downloading TV shows turned watching the screen into an experiment much closer to reading a book and listening to a record than to thrilling in unison.

The online experience is also threatenend by zombie moving images. The web itself is full of tutorials about how to make the most of it; videos in which you can marvel at other people using the Internet. What happens on your screen is a mise en abyme, i.e. a screen within a screen, to update the phrase. The screencast is a substitute for a sensation of being online, an erstaz. There is no possible interaction, the image is locked from the inside. The recorded is a relic of the past, it is like rereading received messages.

You can see the cursor moving, but the hand directing it is not yours. It’s not going where you’d like it to go. It’s not clicking on what you’d like it to click on. Frustration at its best.

The girl in the pink sweater just took more pictures. Of the seat-back screen. Displaying the view of the outside she can’t really see.