The saying “Pics or it didn’t happen” – which refers to the need to document events and to lend authenticity and credibility through media dissemination and/or reproduction – existed before the invention of the Internet. The more mediatised the world becomes, the more the relationship between the screen and the event – and between broadcasting and screencasting – becomes reversed.

Adherents of the media theorist Marshall McLuhan firmly believe that people are unthinkable without their media.1 Human capacities for perception such as seeing have always been expanded by a variety of media, old and new (e. g. the telescope and television). In the 20th century, telegraphy, the telephone, radio, and television turned the world into what is often described as a global village. In 1969, the television screen was the dominant medium. The leading form of media dissemination was broadcasting. The moon landing spectacle, which took place in the same year, was the first major event to be viewed almost simultaneously in living rooms across the (Western) world. Broadcasting allowed spaces to be compressed in such a way that one could be present for events that were in fact taking place almost 400,000 km away. For most human beings, it was the fact that it was transmitted via television screens that made the moon landing into an event that they were able to participate in. In this case, the event and its on-screen transmission become one and the same. The moon landing is actually so closely associated with its appearance on the television screen that conspiracy theorists insist to this day that the moon landing never took place, but was instead staged with the aid of the Hollywood moving picture industry. On the other hand, the television transmission of this event is simultaneously the guarantee and evidence of the event having taken place, in line with Roland Barthes’s dictum of photographic witness: of the “that-has-been.”2 This transmission was also the occasion for screen photography. After all, anyone wishing to show that he or she had been a participant in the transmission of the moon landing had to allow themselves to be photographed next to the television during the broadcast.3 It is no longer the moon landing itself that is the event, but the television transmission of the moon landing: “that-has-been.” In short, a variety of interactions can be made out between the event and the screen. On the one hand, the television transmission produces the evidence of the moon landing as an event that happened in the way it was televised. On the other hand, for all of those citizens of the global village equipped with a television, the television transmission itself becomes the event. Finally, a photographic reproduction of the screen permits one’s own participation in the television event to be reported to others. In this case, broadcasting is the precondition for screenshots (static screen images) or screencasts (moving screen images).4

In contrast to the situation in 1969, we are currently living amid a sea full of screens. We are surrounded by televisions, computer monitors, touchscreens, advertising screens, smartphones and smartwatches, VR headsets, and information screens showing the time, the timetable, the weather, the news etc. One might easily get the impression that the urban environments seen in some megacities are made up of screens as much as they are made up of buildings. Here, screens are always part of media event reproduction. In Hong Kong, for instance, there is a building more than a hundred storeys in height called the International Commerce Center (ICC). Its LED façade is also a screen. The “ICC Light and Music Show” is on show every evening between 7.45pm and 9pm, demonstrating what this screen is capable of doing. Any photograph of this building taken during these periods is therefore also a screenshot. During transmissions of items such as major sporting events, screens are always included in the image: digital billboards, animated LED advertising banners etc. Every broadcasting of these environments is thus always a screencasting of multiple advertising screens, which make the sporting event possible owing to sponsorship. The motto: no screens, no transmission of image.

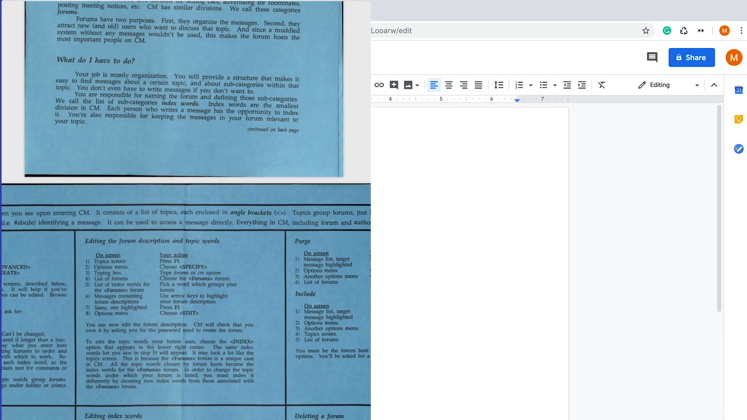

These screens are no longer vicariously showing us what is happening in the world (as in the case of the moon landing). Instead, they have become part of that which happens in our world. A closer look reveals that, in our media-permeated day-to-day lives, we have always been submerged in this hyperreal sea of screens.5 This habitat permits not only a life surrounded by screens, but also a life on and with the screen. It has produced phenomena such as screen-based work and e-learning. Modern startups are made up of teams with members living all over the world. Networked computer screens open up new, topological, software-supported spaces for online meetings and file handling (the data cloud), all organised with the aid of project management software. Paradoxically, the products of this work are often, in fact, digital apps, which communicate with their users via an app. Screenshots and screencasts are the tools of choice for users to show each other what is going on in their own screen environments. In webinars or in learning platforms on the Internet, people learn cultural techniques such as programming or computer game design. Screencasting is always a factor in these practices. Moving or still images of what is taking place on the teacher’s screen are reproduced. What we see there – mouse cursor movements, changes in the image as a result of input – are only the traces of physical activity that takes place in the material region outside of the boundaries of the screen. Primarily, however, screencasts are media transmissions of screen events.

The same applies when we switch from screen-based work to screen-based leisure. We might, for instance, attend a funeral event in World of Warcraft, in order to pay our last respects to a guild member who has died in real life. If this event is attacked by members of another guild as an easy way of levelling up their own characters, this attack is documented by screenshots and screencasts and shared with other users on social media.6 Alongside media representation of simulated violence and crime in online games such as Grand Theft Auto Online or World of Warcraft, screenshots of (for example) trophies gained are created and shared.7 Let’s Play videos are an example of screen-based work and screen-based leisure coinciding: Let’s Players play computer games whilst simultaneously commenting on them and either show them on YouTube at a later time or stream them live on platforms like Twitch (examples include the famous Minecraft series Far Lands Or Bust).8 In contrast to the moon landing, in these cases the screen is neither solely the medium via which an event is communicated, nor the medium through which an event is documented. Here, the screen is the site of the event, and the event actually takes place on the screen.

Finally, there is the case of large-scale e-sports events, which reversed the relationship between the event and its media transmission via a screen. In this context, events that genuinely take place on screens are transferred to the physical context of large multipurpose halls and stadiums, and take place in front of a live audience. The 2015 League of Legends: World Championship Final was watched by 17,500 spectators in Berlin’s Mercedes-Benz Arena. In order to let these spectators participate in the event, the matches are projected onto large cinema screens. These screens are not there solely to show information such as the game scores and the remaining game time, or to screen adverts or to show camera images of events that are physically taking place. Their main function is to principally show the game, as the game is not taking place in any location other than the accumulation of screens located within the hall. Compared with the moon landing, screencasting in this case is the precondition for the broadcasting, making it possible to transfer the match to additional screens outside the hall.